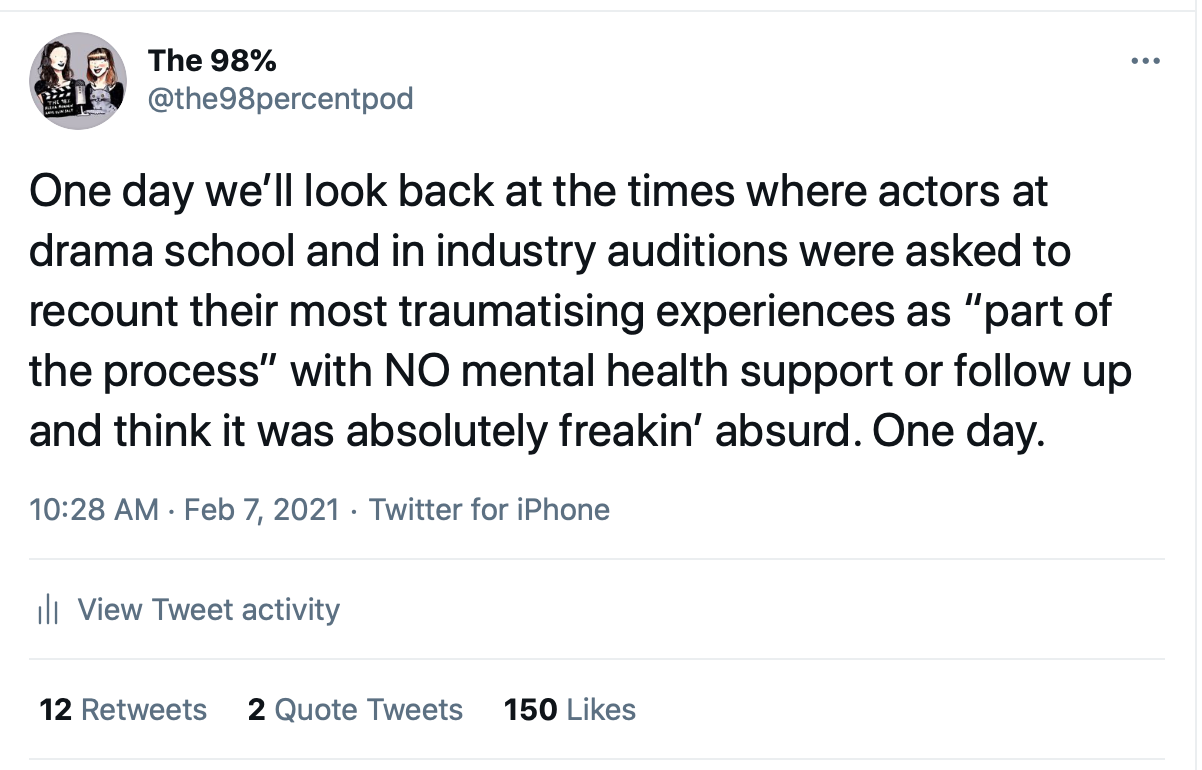

This week, on The 98%’s twitter (@the98percentpod), a listener responded to our tweet saying that he wrote his dissertation on the point we raised. We offered him a space to share an extract from his writing on our blog as it sounded super interested! And so…we present to you….

An investigation into the Ethical Considerations of ‘Method Acting’ and the Importance of Emotional Control in Performance - Extract

By Harvey Westwood

In filming the 1999 autobiographical comedy: ‘Man on the Moon’, actor Jim Carrey adopted an approach to his portrayal of his personal idol, the late comedian Andy Kaufman, that is recognisable as the technique of “Method Acting” pioneered by Lee Strasberg. This is due to his claim to ‘feel’ every emotion his character would feel and become truly inhabited in the character. Strasberg regarded this emphasis on emotion and credible behaviour as a vital process of actor training. Carrey continued to behave as if he were the real Andy Kaufman when not being filmed. He insisted on being referred to as the real ‘Andy’ and went as far as drinking excessively on set, insulting his fellow cast members, and actively goading them to assault him. Jim justified his behaviour by describing the process of ‘becoming’ Andy as akin to a possession. He states in the 2017 documentary on the making of the film: ‘Jim and Andy: The Great Beyond’ that anything that happened after ‘Andy took over to make his film’ was ‘out of his control.’ This process was arguably not only damaging to the wellbeing of Carrey’s cast members, who frequently cited frustration and fatigue with his antics, but also caused Carrey emotional distress when the character was no longer a physical presence in him. Speaking in his own words: “I couldn’t remember who I was anymore, when the movie was over. [...] Suddenly I was so unhappy. And I realised that I was back in my problems. I was back in my heartbreak.”

This process was potentially unnecessary and damaging to the actor and others. Firstly, it is impossible to suggest that Jim did not have a sense of what was happening whilst he was acting, because as the actor behaves as though he is the character and shapes emotions to fit, there is inherent depersonalisation in the performance. Furthermore, the ‘heartbreak’ Jim describes typical of the fantasy proneness and elevated dissociation typical to actors (compared to people in other professions) that leaves them more vulnerable to psychological distress. This is not a trait unique to famous actors, as illuminated by research conducted by Paula Thomson and Victoria S. Jaque that concluded performers have notably higher proneness to depression. In light of this information the appeal of utilising ‘Method’ techniques can be understood, as ‘becoming a character’ provides alluring escapism to the point of a form of addiction. From an anonymous survey of eighteen actors, an individual suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder struggling with Emotion Memory exercises gave me the following account:

“I find it very hard to sometimes separate out my personal anxieties surrounding my PTSD with the performance and stay in control. I once did an exercise where we had to access the first memory that came into our heads from the past year. All I could think of was this specific event and it meant I could not complete the task properly due to being unable to exit the memory and having to relive it [...] It can feel very lonely as you feel no one can understand what you've experienced as well as very overwhelming and vulnerable having to suddenly be so open about it with others.”

This comment draws parallels with research cited in the paper: ‘Responsible care in actor training: effective support for occupational health training in drama schools’ which expresses the concern that there is often little, if any, consideration of students’ innate sensitivities that unwittingly place some actors at higher risk of mental illness. This, compounded by research that concluded actors have been found to exhibit higher rates of fantasy proneness, increased anxiety, and disassociation compared to control groups, suggests that considerations for wellbeing of actors should be a higher priority. Further instances such as these have been documented, such as in the case uncovered by drama researcher Mark Seton of an actress who suffered a nervous breakdown following her strict application of ‘Emotion Memory’ and performance of a notably visceral scene in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ to such brutal excess that the actress developed bruising. It is Seton’s belief that learning appropriate self care and sustainable practice is crucial to surviving and flourishing in the field of performance. Of those eighteen surveyed who had previously taken part in Emotion Memory exercises, twelve expressed the technique had made them experience emotional distress in the past. Perhaps encouragingly, when asked if they felt they received enough aftercare from a teacher as a result, many agreed (60%), but the majority noted that if they were to become traumatised by a role they would turn to friends and peers for emotional support rather than a teacher or director (66% answered friends/peers versus 33% teacher/director). Considering this, alongside the research conducted by Equity in 2013 for The Australian Actors’ Wellbeing Study, for which a high number of actors reported they also primarily use alcohol with friends as a means of ‘unwinding’ rather than regular techniques for cooling down after challenging performances. This leads me to suggest that if powerful teaching techniques are used that encourage actors to ‘connect’ to and ‘feel’ the worlds of their characters, there should be consideration across the board for cooling down and emotional distance in order to avoid developing unhealthy coping mechanisms.

The examples cited above involve diverging circumstances and disparate effects but have similar outcomes. The primary risk of 'The Method' is disillusion and emotional distress from the process of being too physically and emotionally invested in a character to the point where the body has trouble separating the factual emotions uncovered whilst portraying the fictional reality of the character.

In light of these conditions it must be deliberated, given its lionisation in the media, how important ‘The Method’ truly is in delivering an emotionally present and real performance. Is it necessary for an emotional expression to be ‘real’ to be believable? Despite personalised emotional truth remaining the ‘inner Holy Grail’ for the actor, many of The Method’s detractors, among them playwright and director David Mamet, who considered such techniques ‘not only unnecessary but harmful for both the author and the audience’, argue Strasberg’s techniques are not as essential to performance as one may be led to believe. Mamet argues in True and False: Heresy and Common Sense for The Actor that the actor’s job is to portray the words of the author and any emotion genuinely elicited should be seen as a trivial by-product, not the goal, which is to, literally, “pretend”. Though his comments are perhaps intentionally inflammatory and flippant he is supported by the comments of Elly. A Konjin, who argues in Acting Emotions that The Method is built on a ‘conundrumic supposition that an actor can form an empathetic, affective transference with a set of glyphs on paper called a character.’ This does not suggest practitioners of naturalism do not hold any merit. In fact, I would agree with the differing assertion of Stella Adler that utilising imagination to illicit a believable performance is more effective than using one’s limited personal history. However, I do not agree with her belief that the actor’s chosen justification for a character should ‘agitate’ them in order to experience the action and the emotion. As we’ve become aware, this can lead to abuse of power from those in a directorial position. I do not believe a director should ethically be allowed to ‘agitate’ a performer, such as the example of Strasberg tying actress Geraldine Page up to allow her to act like a “trapped animal”. In my view, a powerful performance should be derived from the actor’s research into action, given circumstances, and textual analysis as originally suggested by Stanislavski, rather than ‘prodding and poking at an actor’s feelings’.

It is apparent that whilst many of the foundational principles regarding sense and emotional awareness are important to be studied, it’s irresponsible to suggest it is the one “truthful” method of behaving and it is the teacher or director who is the sole judge of what is considered good performance. Furthermore, the actor should be aware of their own sense of truth rather than the perception of ‘real acting’. Denis Diderot in The Paradox of Acting lays out how he believes the ‘technical quality of affective acting is in inverse proportion to the actor’s identification with the part’. Diderot, in the following passage, compares the actor who ‘plays from the heart’ to the actor who is ‘an attentive mimic’: “If the actor were full, really full of feeling, how could he play the same part twice running with the same spirit and success? Full of fire at the first performance, he would be worn out and cold as marble at the third. [...] The actor who plays from thought, from study of human nature, from constant imitation of some ideal type, from imagination, from memory, will be one and the same at all performances, will always be at his best mark.”

Harvey is an actor, singer, and mental health First-Aider from Bristol. When he's not being quarantined on a Cruise Ship (true story) he's keeping busy by revisiting his illustration passion and looking forward to going to bottomless brunch again! He can be found at @Harvey_Westwood on twitter and @harveywestwoodactor on instagram.